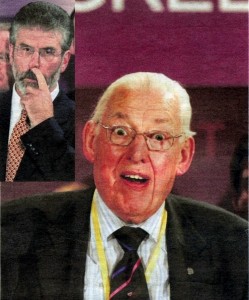

When I was at boarding school in Enniskillen, Northern Ireland during The Troubles, it seemed clear to me Gerry Adams and Ian Paisley were simply two ends of the same candle, one as much to blame for the problems as the other. Of course my opinion was tainted by the fact that Paisley presented himself to be a man of the cloth and I had little time for men of the cloth, while Adams was IRA and I had no time for them, either.

When I was at boarding school in Enniskillen, Northern Ireland during The Troubles, it seemed clear to me Gerry Adams and Ian Paisley were simply two ends of the same candle, one as much to blame for the problems as the other. Of course my opinion was tainted by the fact that Paisley presented himself to be a man of the cloth and I had little time for men of the cloth, while Adams was IRA and I had no time for them, either.

My father, an Irish Protestant from Cavan, could have been very political if he’d wanted to be. The son of an Orangeman, he’d talk about the Twelfth of July as if it were some kind of holiday. To me – raised an unhyphenated-American, the only day in July that warranted any such talk was The Fourth. Even once I understood more about what the Twelfth was about, I questioned its real purpose. After all, to me it was rubbing a historical defeat in the face of those defeated and that was bound to lead to trouble.

My mother, on the other hand, had a rarely used but far sharper opinion on the matter. Paisley was an idiot, a troublemaker, she thought; Adams an opportunist, and both had real blood on their hands.

By the time I left Northern Ireland in 1981, I’d seen too much foolishness, suffered too much hatred to ever want to return. Mom said, “Son, they can’t help but hate each other. How can you expect them to hate you any less?”

It wasn’t until 1992 that I broke my vow and returned to Northern Ireland for a night, but since then I’ve been back and over the years my feeling towards the country and people has changed for the better. I faced some of the darkest ghosts of my past and found that in doing so they no longer had any power over me.

I’m currently reading Gerry Adams’ autobiography, “Before the Dawn”. I haven’t finished with it yet, but even if I didn’t know anything at all about Irish history and politics, I’m far enough along to wonder how he could have fooled so many to get behind him. Or maybe he was a pawn, I don’t know but I don’t feel enlightened. Thus far his influence seems to center on the defiance of flying a tri-color, the riots that ensued, and his confusion over having to write “British” for nationality on a government form. Maybe as the book goes on he’ll delve into some real cause, but for now his childhood seems surprisingly comfortable and worry free given the struggles and oppression he so often talks about.

He does make one point I can relate to – about having to learn British history. At Portora Royal School in Enniskillen I learned British history, and what bothered me most about it was the notion that, somehow, Britain was the center of the universe and that anywhere else either didn’t exist or was still a colony. I never took American history so I’ve no way to compare, but some folks still referred to America as The Colonies. A joke, I hoped, but the way some people said it with a high and mighty what-what British accent and attitude, there was plenty of reason for doubt.

Irish terrorism, however, was no joke. In October 1976 the IRA machine-gunned a member of my family as he worked the counter in a butcher’s shop. I was young and the killing happened so far away that it had little impact on me at the time. All that changed in November 1977 while I was at my grandmother’s house in Ballygawley, Co. Tyrone. Around seven in the morning an almighty blast reverberated through the house and, almost immediately, I heard screams of “Jesus Christ” and “Somebody’s dead. Somebody’s been killed” from all around. I threw on my jeans and a shirt and some shoes and sprinted the hundred yards or so to what remained of a lorry parked at the side of the road, its driver blown clear, gravely wounded but still alive. And I remember the red smudge I got on my sneaker and how now matter how hard I tried I couldn’t get it to rub off. But what I remember most is what seemed like the slight curl of a smile on too many faces in the gathered crowd.

There were other reasons to hate the IRA – the La Mon attack near Belfast in February 1978. The newspapers had a field day at the time, even publishing pictures of the charred corpses. I suppose it was for shock value, but I wasn’t shocked. I didn’t feel much of anything.

In November of that same year, a bomb exploded in Enniskillen. Even from several miles away the blast was powerful enough to shift my bed several inches from the wall and fill the room with a fog of dust. Some in the dorm speculated they’d bombed the Killyhevlin Hotel a few miles out on the other side of Enniskillen, and I hoped my friend Richard Watson’s family who owned the hotel was okay. It turned out the IRA blew up the new library (the Killyhevlin was blown up in 1996).

Over the summer 1979 the IRA killed a friend of mine, Paul Maxwell, using 50lbs of explosives put aboard the boat he was working the summer. Killed some others, too, including Lord Mountbatten, the intended target. That day the IRA also killed eighteen British soldiers at Warrenpoint. At the time the IRA hailed these attacks as great victories. “13 Gone But Not Forgotten, We Got 18 and Mountbatten,” could be seen where you’d expect. Apparently the supporters didn’t count the others killed that day.

Ian Paisley spearheaded the condemnation; spewing rhetoric and religion out of both sides of his mouth every chance he got, constantly reminding me of the devil as he did so.

Decades later, in 2001, I returned to Northern Ireland after they had attained “peace” and I was very happy to see just how much had changed, at least on the surface. Gone were the roadblocks and checkpoints and much of the barbed wire that had been a common fixture for so long. Gone, too, were the concrete security barriers from Enniskillen. Traffic now flowed freely through the town. Side streets that once led to more gray grimness now were treelined and featured quaint cafes and a sense of civilization.

But it was in the pubs I got a sense of how things really were. The Protestant pub in Ballygawley, a dingy depressing place with no music, no fun, no life; the Roman Catholic pub at the top of the town bristling with entertainment, laughter, dancing. In there I got talking with some of the locals and asked how they thought things were. “Fine,” they said. “But we keep the guns across the boarder for when the hunting gets good again.” These fellows weren’t showing off for an American tourist – they knew who I was, my family, my history. They weren’t trying to be funny. At the appointed time the bell rang, the crowd jumped to its feet and joined the band in the Irish national anthem. I was tempted to burst out with God Save the Queen but decided I hadn’t enough good Irish drink in me to be that stupid.

I was back in Ireland in 2006, this time in the Irish Republic, and saw things were pretty much unchanged. I got talking to the folks in The Molly Maguires in Ballyconnell, Co. Cavan and they were a fun lot. And at closing time it was jump up and sing the Irish national anthem, just like in Northern Ireland.

I went down the next afternoon and asked if any of them knew anything about Nixon Lodge – the local Orange Order, but they all said no. Then the proprietor asked if I knew much about the history of Ireland. Being the wise man, I said no, that I knew only a little bit. The proprietor then began, quite friendly like, explaining the politics and conflict from a republican point of view. I listened intently to his every word. Whether he was full of shite or not didn’t matter – he spoke passionately and eloquently about his beliefs.

Later that night the place was packed with people who’d come to see a local celebrity performer. He played guitar backed by an electronic band, and he sang, too. “He plays songs about the good old days of struggle,” a girl said to me just as the fellow started into some tune about some guy who was put away in prison for a long time and won’t be forgotten because he’s a hero. I smiled politely and kept my mouth shut.

Now, five years later, I’m reading Gerry Adams’ autobiography and trying to keep an open mind. I figure if I could return to Ireland of my own free will, I can read Gerry’s book and, who knows, I might even learn something. If not I’m sure I can find something by Paisley for balance. LOL